Create impact through A/B tests and pilots!

When product experimentation is essential

You’re reading Think clearly, do better. Become a high precision product builder using my insights. Typically grounded in economic theory and always pragmatic.

This post is based on a course I taught in 2021, aimed at early career builders who are new to building - if you want the slides version, DM me on Substack.

You’ve just started your first product role. Your manager asks, “Should we build feature X or feature Y?” You have opinions. The engineering partner has opinions. The designer has opinions. Sales has opinions. The manager on a partner team that will write your peer review has opinions. Everyone sounds convincing. How do you actually decide without spinning in debates and analysis paralysis forever?

This is where experimentation can become your superpower. But here’s what most new product builders miss: not every decision needs an experiment, and knowing which type of experiment to run matters as much as running one at all. When you have thousands or hundreds of thousands of customers, making decisions on intuition alone is a recipe for a worse customer experience and revenue loss. Experimentation is the mechanism by which builders can define and evaluate assumptions about the product and customers. By the end of this post, you’ll have a decision framework that will serve you throughout your career.

Experimentation is the mechanism by which builders can define and evaluate assumptions about the product and customers.

Let’s dive into the fundamentals of experimentation, how builders can shape it, and the different forms these tests take.

Why experiment?

Experimentation moves decision-making away from guesses with unknown probability of succeeding and toward greater certainty. The business benefits from experimentation in several ways and you may not realize it yet, but when you’re operating at scale, you can experiment your way into growing a product:

Setting the roadmap: When you are unsure what steps to take next, experimentation helps build out the roadmap, product specifications, and requirements documents by driving decisions through structured discovery.

Managing stakeholders: Experiments are crucial for breaking opinion-based ties. If your sales, engineering or other stakeholder groups aren’t bought in on what to do, testing provides objective data to move forward.

Making launch decisions: Experimentation helps find the best choice among several alternatives. It guides you to make high-quality decisions about when to launch.

Building brand and credibility: Presenting your rationale to leadership or externally to customers and partners requires strong justification. Running structured tests helps you build and maintain credibility, especially when you or your team are new to a role.

When to experiment

Not every decision requires an experiment, though. Here’s a framework for deciding:

Skip the experiment when:

The change is reversible and low cost. If you can easily roll back and the downside is minimal, just ship it and monitor metrics. For example, changing help text or adjusting a tooltip rarely needs pre-validation.

You’re fixing something obviously broken. If your checkout flow crashes for 10% of users, you don’t need to A/B test the fix. Just fix it.

You have overwhelming evidence from similar contexts. If five competitors have proven something works and you’re in an identical market, you will be better off putting something in front of customers and learning directly.

The cost of running the experiment exceeds the value of the information. Sometimes, setting up the experiment infrastructure and waiting to collect data takes longer than building the feature itself.

Run an experiment when:

The decision involves significant build investment. Before committing weeks or months of development time, validate that users want what you’re planning to build.

The change could negatively impact key metrics. Any time you’re touching core flows - signup, checkout, content consumption - you should validate that you’re not introducing friction.

You’re choosing between competing hypotheses. When smart people disagree about what will work, let data break the tie.

You need to quantify the impact. Even if you’re confident something will help, experimentation tells you how much it helps, which informs prioritization.

You’re in a competitive market and need to optimize relentlessly. In ads, social media, e-commerce - small improvements compound. Experimentation becomes a competitive advantage. I’ve built a career off of shipping experiments in online ads.

Driving clarity and operationalizing

The product builder is central to the success of any experiment. With AI, role responsibilities are evolving but the breakdown below will still apply to any product building pod, however it’s constructed in 2026+. The pod still needs to:

Articulate the goal and hypothesis.

Articulate the success criterion.

Drive momentum among contributors or functions so the test can start and run effectively.

Analyze the data collected and in cases of A/B tests run, dive deep into what the experiment reveals about the larger customer base.

Build a pipeline of on-the-ground pain points and partner in spotting friction from feature ideas upfront.

Identify a shortlist of customers (eg when running pilots), inform the hypothesis you want to probe into, and validate market-facing conclusions with any intermediaries involved in getting the product to market.

The more fluent you are about the customer base, the more likely you are to come up with high utility experiments. For B2B or enterprise products, this means articulating the canonical companies you service, the roles of both the end user and fiscal buyer, and the common friction points and unmet needs. For B2C products, this requires articulating psychographic and/or demographic traits of target users, high-level descriptive statistics (like engagement, retention, and churn rate), and typical Customer Usage Journeys (CUJs).

Two forms of experimentation

You’ll find over time that experimentation generally takes two forms: quantitative and qualitative.

Quantitative experimentation: A/B testing

Quantitative testing, often presents as A/B testing, focuses on measuring concrete metrics. This includes A/A tests, A/B tests, and multivariate tests. A/A tests are run for data hygiene reasons, mainly, to make sure there aren’t any skews in your A/B testing infrastructure that would cause you to measure an increase/decrease that isn’t present. A/B tests divert your users into two groups: “control” experience and “treatment” where the hypothesis, like a new page layout, is tested. Multivariate experiments test more than one treatment arm.

Before running a test, you must define the experiment and its goal. This starts with a strong hypothesis that’s:

falsifiable

actionable

quantifiable

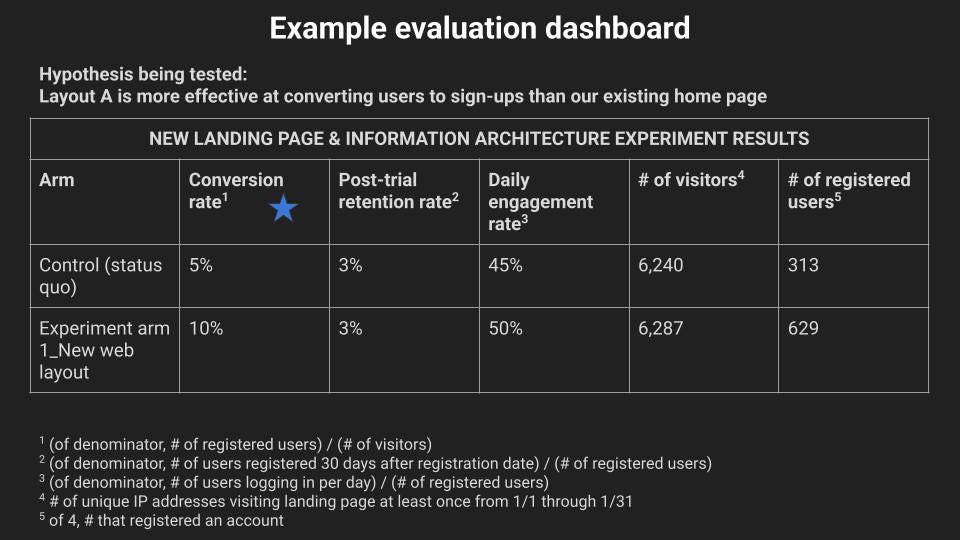

For example, a strong hypothesis might be: “Layout A is more effective at converting users to sign-ups than our existing home page” and your success metrics will help reveal the effect of that change:

Defining success metrics

When evaluating results, absolute changes alone are generally not interesting. We care about rates of change like MoM, YoY, or percentage difference between groups because you’re trying to figure out if the change, like “Layout A” is changing customer behavior so that the product is more likely to succeed. If you have customers using your product, there’s already a baseline percentage of eg conversions and retention.

Typical key metrics to track:

revenue (often measured by MoM or other period-over-period revenue growth)

retention: such as spending customer retention or post-trial user retention rate

churn: this is the complement of retention, eg if retention is 10% then 90% of users churn.

engagement: often tracked through M/D/WAU (monthly/daily/weekly active users) or session duration. The product defines what “active” means (e.g. logs in once, completes a transaction, watches a video to completion).

Qualitative experimentation: pilots and voice of customer

Qualitative methods, such as pilots (alphas, betas), are particularly well-suited to early-stage products and B2B environments. These pilots are run to test the fit for an MVP or an early version of your product without making the full, more costly investment in product quality and commercialization.

Pilots may be internal (to learn about fit among sales teams) or external (to test fit with real existing or target customers). A classic example is Rent the Runway (RTR), which was founded on the critical assumption that renting formal evening wear could be a mainstream practice. To clarify customer demand uncertainty, founders ran pilots, including in-person showcases and e-mailing PDFs of inventory. Learnings included validation of interest through attendance, revealed preferences from resulting rentals, and free-form feedback.

Regardless of the pilot structure, always collect feedback quickly - surveys provide summaries, but quotes are powerful. This firsthand experience strengthens your customer empathy and ability to make decisions on their behalf.

Gathering the Voice of Customer (VoC) involves a systematic process: interview, record, transcribe, list Wants and Needs, and finally Extract/Sort by themes to create a Hierarchy of Needs. When conducting these interviews, it is crucial to approach the conversation as an ethnographer, listening without bias, and making cultural inferences from what people say, how they act, and the artifacts they use.

How to choose the right experiment type

Here’s a decision tree to guide you:

Start here: do you even need to validate the idea?

If no → just ship it and monitor

If yes → continue

Have you built anything yet?

No → consider fake door testing to validate demand

Yes → continue

Do you need to understand why users behave a certain way?

No → continue

Yes → pilots or observational studies

Do you have enough traffic for statistical significance?

No → pilots or observational studies

Yes → continue

Testing one thing or multiple variables?

One thing → A/B test

Multiple things that might interact → multivariate test (if you have high enough traffic and/or time)

Concerned about long-term effects?

No → standard A/B test is sufficient

Yes → run A/B tests with long-running holdback tests. A holdback test keeps a portion of your user base on the previous version of the product so that you can reference how customers are behaving and engaging with your product through seasonal effects.

Common mistakes to avoid

Mistake 1: testing without a clear hypothesis

“Let’s try making the button blue and see what happens.” → “We hypothesize that changing the button from green to blue will increase clicks by 10% because blue is a more standard action color and our users are conditioned to associate it with CTAs from other products they use.”

Mistake 2: changing your mind mid-experiment

Resist the temptation to extend an experiment that’s not reaching significance or to stop early when results look good. These behaviors inflate false positives.

Mistake 3: ignoring practical significance

Statistical significance is not the same as practical significance. A 0.5% improvement that’s statistically significant might not be worth the engineering effort to maintain two code paths.

Mistake 4: not considering the user experience

Running too many experiments simultaneously can degrade the experience for customers. Coordinate with other teams to avoid showing users too many experimental variations at once, especially when you have multi-step journeys.

Mistake 5: treating experiments as the only input

Experiments are powerful but they’re just one input to decisions. Combine them with:

customer feedback and qualitative research

technical feasibility and maintenance cost

strategic alignment with long-term goals

competitive landscape analysis

Do now, on your first set of projects

Map your upcoming features to the decision tree in this post. For each feature on your roadmap, determine whether it needs validation and which experiment type is appropriate.

start documenting opportunities for experimentation. Even if you’re not running formal experiments yet, practice writing hypotheses for the decisions your team is making.

audit your team’s experiment infrastructure. Do you have the tools needed to run A/B tests? If not, this should be a priority conversation with engineering.

pick one small decision you’re facing right now and design a simple A/B test for it. Aim to launch it within two weeks.

review a past decision your team made without experimentation. Could it have benefited from validation? What type of experiment would have been appropriate? Use this as a learning opportunity to sharpen your judgment.

find an experimentation mentor either within your company or your network. Someone who has run several experiments that have launched can help you avoid common pitfalls and accelerate your learning.

Conclusion: take bolder bets and achieve them

Experimentation is meant to help you get to success faster and more efficiently - whether you define it as a product spec worth $1B of adoption or an incremental increase in user retention.

Disclosure: this post was written with the help of AI.

If you’ve made it all the way to the bottom, thanks for reading “Think clearly, do better”! Consider forwarding to someone who may find it useful.