Avoid logical fallacies

Why what sounds good can lead to bad product, bad decisions

You’re reading Think clearly, do better. Become a high precision product builder using my insights. Typically grounded in economic theory and always pragmatic.

I was in a review where sales wanted to know more about how the product was built. “…Why doesn’t the backend need a warning message to be set? But in the other product this setting is required….” Not only were the questions probing into a level of detail that’s not what customers ask about, they were building up a case implying a lack of readiness to go to market, preventing us from launch and moving forward at all. But that, an explanation of technical design, was a red herring - a common logical fallacy. As soon as I recognized it, I steered the discussion to ask what the minimum amount of information necessary for sales is instead of continuing to debate whether product performance or the design needs to be explained.

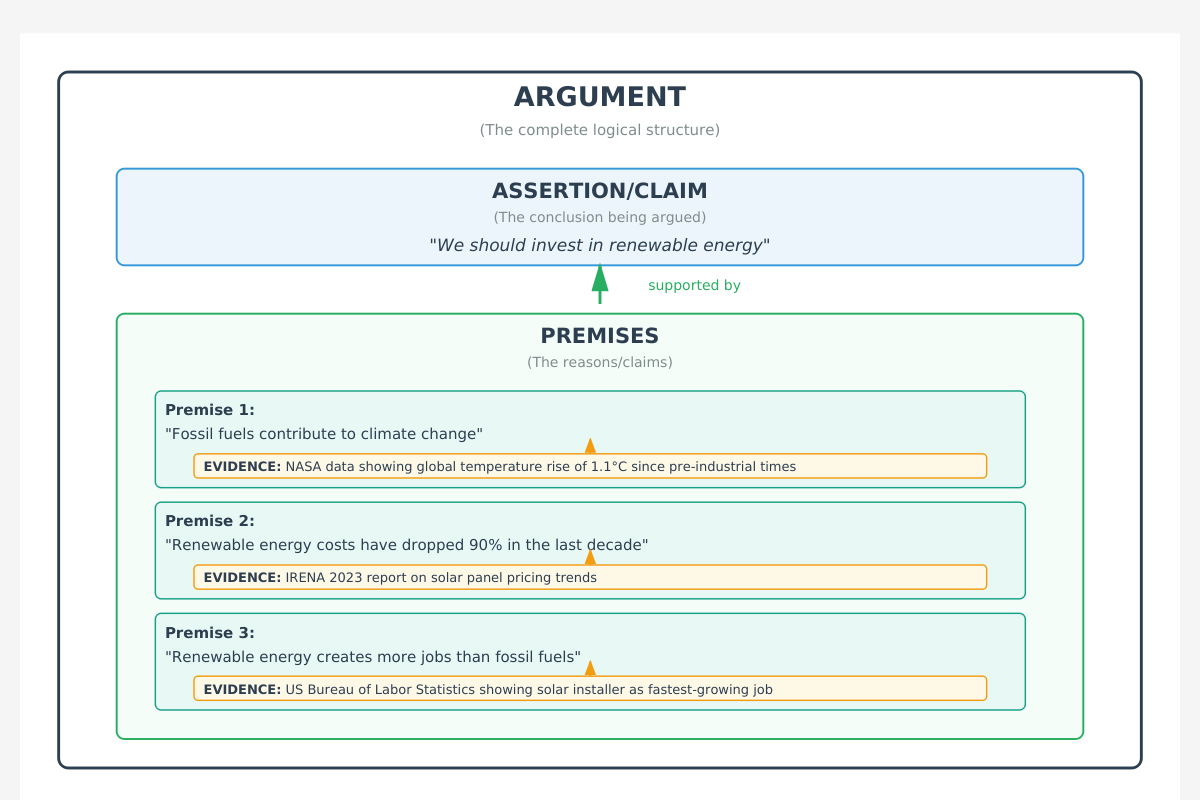

A part of thinking clearly is being able to reason well and examine when others don’t. We are surrounded by attempts at shaping our perception - things can often sound good, even when they’re not true. Logical fallacies are mistakes in the chain of things that must hold for an assertion to be true. See the diagram below on the evidence, premise, assertion structure that makes up arguments.

When someone says something that isn’t a simple observation (eg “She sent the marketing newsletter today”) or describing how they feel, they’re usually linking multiple points together to make an argument. Once you understand what they are, you’ll find that logical fallacies are everywhere! They’re used in heated arguments, by marketing campaigns, sometimes without intention, and often to persuade you.

When I first started in Product Management, my superpower, clarity of mind, led me to name these flaws in reasoning. That doesn’t work with all audiences (though usually received well by engineers) and sometimes adds unnecessary strain by shifting folks to semantic debates. Almost in no regular context will naming the logical fallacy cause the other party to stop using it, but it will help you to not make decisions under the influence.

Examples of logical fallacies:

1. Begging the question:

Sounds like “this project has a higher chance of working out than the other one because it’s better”.

Why it doesn’t work: The conclusion of project A being better than project B is a circular reference to its higher chance of success. There’s no explanation for why project A has a higher chance of success. The statement assumes what it’s trying to prove. “Better” and “higher chance of working out” are essentially the same claim. What makes it better? Is it better aligned with customer needs? Does it require fewer resources? Is the technical risk lower?

2. Ad hominem:

Sounds like:

Teammate A: “I’m worried about the scalability of this product. I’m concerned we’ll hit performance issues at 20 concurrent users, and the sales projections show we’re targeting 100 by Q3.”

Teammate B responds: “Look, you’ve only been here six months and this is your first B2B product. Those of us who’ve been building enterprise software for years know that these projections never materialize the way sales thinks they will. Let’s move on to the next topic.”

Why it doesn’t work: Teammate B critiqued the person’s experience and tenure instead of addressing the actual technical concern about scalability. Whether the engineer has been there six months or six years doesn’t change the validity of the test data or the gap between current capacity and sales targets. It sounds like good reasoning (albeit rude) but it has weaknesses. The new teammate might be right. Those tests might reveal a real constraint that needs solving before launch. Don’t take critiques on a person at face value - question what motive the speaker might have for the conclusion to be believed.

3. Bandwagon fallacy:

Sounds like “everyone nodded along when he was speaking, must mean it’s a good idea”.

Why it doesn’t work: Assumes the idea is good because of its acceptance rather than on its own merits or supporting evidence. It could be that folks are nodding along because it is easier than disagreeing, that they want the discussion to move along, or that they are not thinking critically. Often used as a tool to get your approval on a proposal, etc.

4. Red herring:

Sounds like “He didn’t launch the feature, he left the office in the late afternoon”.

Why it doesn’t work: What does leaving the office have to do with launching a feature? If you’ve ever launched something, you know that the requirements are a computer, code, alignment, internet and approvals. It skips a few steps of reasoning, letting your imagination fill in the steps between a premise and a conclusion that isn’t actually supported.

5. False dichotomy:

Sounds like “Do you think customers want to buy the blue shirt or the large one? Blue is a widely liked color but large shirts are more comfortable”.

Why it doesn’t work: Why are those the only two options? It’s a useful rhetorical tool but don’t interpret it as fact. The two options falsely frame the decisions as binary when there may actually be many other possibilities. You can overcome the limited framing by bringing up examples of other product offerings that you’ve seen in market (eg patterned shirts) or may work. Whenever you hear a forced choice, pause and ask: are these really the other paths forward? Are these even paths or are they rhetoric?

6. False analogy:

Sounds like “We need to treat this feature launch like a rocket ship - get all the pieces perfect because we only get one shot at liftoff.”

Why it doesn’t work: There are crucial differences between the development-side controls available for launching a product feature and a rocket ship that make the comparison invalid. While there are some similarities like both are well-planned, timed events that require collaboration across teams, software can be rolled back. A rocket ship cannot. The statement is creating an exaggerated sense of risk by implying that the two are similar in all respects because they share a few similarities.

7. Hasty generalization:

Sounds like “Our last feature launch failed because users didn’t engage with it. Obviously, our users don’t want new features—we should just focus on maintenance and bug fixes from now on.”

Why it doesn’t work: This is a sweeping conclusion from one feature’s launch. On its own and without context about the rest of the product and the user base, it fails scrutiny. What if the feature solved the wrong problem? What if the onboarding experience was confusing? What if you launched it to the wrong customer segment? What if the timing conflicted with another major change?

8. Strawman argument:

Sounds like:

PM A says: “I think we should spend two weeks doing proper user research before committing to this redesign. We don’t have clear evidence that users actually want these changes.”

PM B responds: “So you’re saying we should never ship anything without months of perfect research? That we should just sit around interviewing users forever instead of building? We’d never launch anything if we followed that approach.”

Why it doesn’t work: When you misrepresent someone’s position to make it easier to dismiss, you’re not winning the debate. You’re avoiding the actual conversation that needs to happen. This conversation is actually about what each PM considers sufficient evidence - they seem to have different bars and/or access to different sources of information. PM A might be right. Maybe there isn’t actually clear evidence about what users want. Maybe two weeks of research would save you months of building the wrong thing. After this debate and eventual alignment on what ought to be the near-term goal and get built, your team should just do the work of building. But you can’t get to real alignment by battling straw men. You get there by responding to what’s actually happening—not your interpretation of what’s threatening your roadmap.

9. Circular argument:

Sounds like:

PM: “Why should we prioritize this feature on the roadmap?” Stakeholder: “Because it’s our top priority for Q2.” PM: “But why is it the top priority?” Stakeholder: “Because it’s the most important thing we need to build right now.” PM: “What makes it the most important?” Stakeholder: “It’s what we’ve decided to prioritize for this quarter.”

Why it doesn’t work: The conclusion (this feature is a priority) is being used as the premise (because it’s a priority). There’s no actual evidence, no customer data, no business impact, no strategic rationale—just a loop that goes nowhere. The stakeholder in this example never answered the actual question. They just restated the same assertion in different words. “It’s a priority” → “It’s most important” → “We decided to prioritize it.” These are all the same claim dressed up as different reasons.

10. Affirming the consequent:

Sounds like: “PM in a post-launch review: “We know this feature is successful because engagement is up 15% this quarter. All successful features drive engagement increases. Our engagement went up. Therefore, our feature was successful.”

Why this doesn’t work: This is affirming the consequent—a logical fallacy that confuses correlation with causation by working backward from an outcome. The logic goes: If A (successful feature), then B (engagement increase). We observed B (engagement increase). Therefore, A (successful feature). But that’s backwards reasoning.

The real skill isn’t in naming fallacies—it’s in recognizing when flawed reasoning is about to derail a decision that matters and shape your / your team’s perception of reality. The next time you’re in a meeting and something sounds too good to be true or confusing, pause. Ask yourself: what’s the actual chain of logic here? What evidence is being offered? What’s being assumed?

You don’t need to call out the fallacy by name. You just need to ask the right question. “What evidence do we have for that?” “Are there other factors we should consider?” “What would need to be true for this to work?” These questions cut through faulty reasoning and gel a team towards a unified direction.

Thinking clearly means building the discipline to catch these patterns—in others’ arguments and, more importantly, in your own. Because the cost of a decision made under flawed reasoning isn’t just that you were wrong. It’s all the time, resources, and momentum you spent going in the wrong direction. Teams that move past the fallacies have the conversations they really need, like about differences in frames of reference, priorities, and expectations.

Disclosure: this post was written with the help of AI.

If you’ve made it all the way to the bottom, thanks for reading “Think clearly, do better”! Consider forwarding to someone who may find it useful.